Five Medals, His Life & Times

Five Medals. Some folks who frequent this website are familiar with the name. Some are not. For those who are, some only know the words or have been to an event up in Indiana that carries the name, but that is the extent of their recognition. This blog is the perfect place to expand on our understanding and share a little history, both recent and distant. Special thanks go to Frank Jarboe (Parson John) for creating and maintaining this valuable website which is serving our Living History family so well.

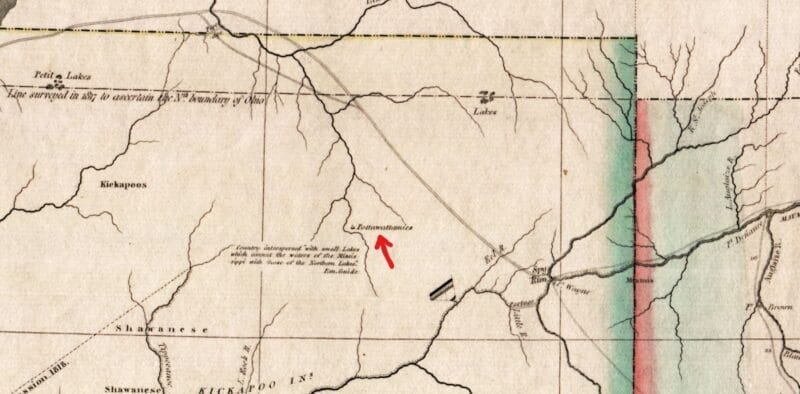

Five Medals is two things. He is a person. It is a living history event. Five Medals was a prominent Potawatomi chief whose village was on the Elkhart River in Northern Indiana, south of present-day Goshen. He was deeply immersed into the rapidly changing world of NW Ohio and Northern Indiana from about 1790 through 1818. He was a peer to Mihšihkinaahkwa (Little Turtle), Buckongahelas, Blue Jacket, Tecumseh, Wahbememe (White Pigeon), Topinabee, and both of the Winamac’s who are constantly confused with each other.

Five Medals, or Wonongaseah, had become a mere footnote to history and in 2009, two historians, one professional and one an amateur, resurrected his name and chose to use it to headline a new living history event. The event has gone through some evolutions. Originally “Gathering at Five Medals” was held on a county park’s property. The event was retired in 2019 and in 2021 emerged on private property, incorporated as a non-profit and under the leadership of one of the original founders plus several legacy participants. Five Medals at The Trace has had a successful four year run and is ready for the next evolution. The name will soon be abbreviated to simply “Five Medals” and, as of this writing, a very exciting announcement is being prepared. Two highlights in the life of the event, and examples of how the leadership of Five Medals is constantly looking for unique ways to share history, came in 2013 and in 2021. Those will be referenced within the following paragraphs.

The challenge and frustration of researching Native leaders is finding information. Are there 50 more journals or letters out there which reference our guy, are there only 4, or are there none? Plus, one source often contradicts another. Then, there’s legend which may contain a kernel of truth and then, there’s pure fiction. The trick is to recognize fiction and to find the kernel in legend. It’s a constant process so, we keep our eyes and ears open and pieces of information continue to trickle in. After 15 years of research, the fact that gives this blogger a sense of accomplishment is that the composite amount of compiled data is greater than any single researcher has previously published. It is indeed amazing how much we now know or can logically piece together, and this blog reveals only a fraction of it, but there’s also much we still don’t know.

For example, we do not have any surviving images of Five Medals. We don’t know for sure when and where he was born but the consensus is 1760 in Southern Michigan, likely the Detroit area. We don’t know who his parents were. We don’t know his wife’s name and only have a soldier’s 1872 memoirs that reference a wife. We don’t know how many children he had, though we’ve seen mention of at least two sons on a document dated 1804. We DO know he had a brother named Oss-Meet because he shows up on the 1821 Treaty of Chicago signatory page and is identified as Five Medals’ brother. We don’t know his date of death. There’s a been a broad range posited. 1820-1829. This blogger leans to 1820. Place of death is likely the Detroit area.

Here’s the story of what we do know. A huge discovery, recently made, is that we know the location of his village. We’ve learned that his name and its source is an enigma and has suffered through a variety of spellings and pronunciations, often due to how a translator and then a scribe heard it and phonetically spelled it. Wonongaseah is preferred but Noungeesai, Onaxa, Onocksey, Waweegshe and Waugshe have all been seen on various documents and in history books.

Wonongaseah translates as 5 Medals or 5 Coins and one theory is that it resulted from all the peace medals he collected from first the British and then, the Americans, which then leads to the question: what was his name before he was a chief and collecting all the hardware? Based on oral tradition shared with this blogger, Wonongaseah, translated to Five Medals, would have been his name from a very young age.

Along the way, 5M signed 6 Treaties of either Peace or Land Cession. The Treaty of Greenville is where his name first appears in history and that occurred in 1795, He also signed The Treaties of Fort Wayne in 1803 and 1809, a second Treaty of Greenville in 1814, Spring Wells in 1815 and St. Mary’s in 1818.

His prominence was such that he accompanied Little Turtle to meet both Presidents Washington in Philadelphia in 1796 and Jefferson in Washington in 1801/02. As a testament to the high regard these men were held, it was customary for the Secretary of War to act as the president’s emissary and meet with visiting chiefs. The Indian Agency was part of the War Department. But, in 1801/02, Jefferson himself met with LT and 5M. Here are Chief Five Medal’s words to President Thomas Jefferson on 4 January, 1802, as transcribed: “Father, listen to your children. Your children are happy that the Great Spirit has given them permission to speak to you this day. Father, your children have travelled a great distance and are happy to meet you at the Great Council of the Sixteen Fires. Father, your children have something to communicate which they think of importance, both to your children the Red People and to you. As the Great Spirit made both, your children hope that no accident will happen to destroy the friendship and good understanding which exists between them and their Brothers, the White People. Father, our Brother, Chief Little Turtle, will communicate to you our wishes and desires.”

On that trip, Five Medals also visited Baltimore and met with Quaker leaders in an attempt to bring updated agricultural equipment and techniques to his home village. This was after the Indian Wars of the 1790’s and 10 years before a resurgence of hostilities in our region here in the northern part of the Indiana Territory. He and other chiefs with whom he was allied clearly recognized the future that lay ahead and were attempting to provide better conditions and food sustainability for their villages, as well as assimilate into what would become a European-American dominated society.

But there was a long row to hoe before realizing that dream, which ultimately was never realized. The actual seeds for the future were planted during the Indian Wars of the 1790’s and they were germinated in about 1805 by the emergence of a Shawnee leader named Tenskwatawa, a.k.a. The Prophet.

The 1790’s were chaotic. In the years following the Revolution, hostilities were ongoing throughout Ohio and Kentucky resulting in over 1500 deaths among white settlers and though unrecorded, certainly a significant number among Native Americans prior to 1789. Then things really heated up. One of the earliest large-scale armed conflicts occurred during October of 1790 when General Joseph Harmar brought his 1400 troops North toward Little Turtle’s town of Kekionga, near present-day Fort Wayne. LT, and the Shawnee chief Blue Jacket were waiting with 1000 warriors. For this time and place, this was a big battle! The Natives dealt a resounding defeat to the Americans and inflicted around 370 casualties. One segment of the battle was when a detachment of Americans led by Colonel John Hardin moved toward the Eel River near present-day U.S. 33 and Carroll Road, just North of present-day Fort Wayne. It evokes visions of a classic B Western. Native scouts sent out as decoys lured Hardin’s troops right into an ambush. He suffered enormous losses of men and supplies. U.S. Regulars and militia were fleeing the field or hiding in the marshes. While there is no mention of Five Medals in anything that’s been studied to-date, it would be ludicrous to think he was not present. Potawatomi’s are mentioned in reports as being present. Author George Ironstack wrote that the Miami [women and children] moved to the Potawatomi villages on the Elkhart River, which at that time was Five Medals’ Village. It was only 20 miles distant and owing to Five Medal’s alliance to Little Turtle and the fact that an adversary was on the main travel route between the village and Kekionga, its farfetched to believe his village filled with warriors was held in check.

Subsequent to Harmar’s defeat, it only got worse for the Americans. An aging and ill Revolutionary War veteran, General Arthur St. Clair took command of a re-provisioned army and in early November, 1791 arrived at present day Fort Recovery, Ohio on the Wabash River. A second large scale battle was about to ensue as similar numbers to the Harmar battle were involved. Who do we see leading the 1000-man Native confederation? The brilliant tactician Little Turtle, Blue Jacket and another renowned Native leader, the Delaware Chief, Buckongahelas. It was a literal massacre. The worst defeat of any American army by Native forces and arguably the worst defeat on a percentage basis of any U.S. force. The Natives suffered an estimated 60 casualties. U.S. troops, 935 at an approximate 67% casualty rate! Again, there is no evidence that Five Medals was present at this battle, but this incident led to General Anthony Wayne taking command of the U.S. forces, realigning them into the Legion of the United States, implementing a rigid training program and returning to the region on the third expedition in 4 years. On August 20, 1794 at the Battle of Fallen Timbers near present-day Toledo, Ohio, the results of Wayne’s leadership were amplified. This time, Federal forces prevailed and the tide was changed forever. Five Medals was present that day and again in Greenville, Ohio on August 3, 1795, when his mark, by his hand, and the symbol on the Five Medals event letterhead and facebook page was affixed to a landmark treaty. One of the observations we can make from studying the roster of participants of that day is that he would be in the presence of men like, Anthony Wayne, Wayne’s adjutant William Henry Harrison, with whom Five Medals would have a long association, and other notable historical figures like William Wells, William Clark and Meriwether Lewis.

At the 2021 Five Medals event, several participants prepared for and reenacted a living image depicting Howard Christy’s famous painting of the signing of the Treaty of Greenville which hangs in the Ohio statehouse! An exact replica of the wampum belt originally presented to General Anthony Wayne by Chief Little Turtle was used.

But, the relative peace was short lived. With the western migration of European-Americans and the emergence of The Prophet and his brother, Tecumseh, the western territory was a pressure cooker. The story of the years leading up to the Battle of Tippecanoe is better told elsewhere but it is vital to mention here because it was arguably the genesis of the War of 1812 in Indiana.

Events were happening in quick succession after November 7, 1811 and on June 18, 1812 the U.S. declared war on Great Britain. In Chicago, at the future intersection of Michigan and Wacker stood U.S. Fort Dearborn. In August of 1812, the Potawatomi’s, led by Pro-British chiefs were congregating there and threatening the fort. Word arrived at Fort Wayne of the fort’s peril and Captain William Wells was dispatched with orders to resolve the situation. Five Medals and Wells had known each other since at least 1795, probably earlier, and Wells had served as Indian Agent at Fort Wayne from 1795-1809. Wells had fought with the Native forces at Harmar’s and St. Clair’s defeats, but with American forces at Fallen Timbers and remained torn between those two worlds. His story is an entire blog unto itself. In the background of this mounting conflict, Five Medals was very outspoken in opposition to Tecumseh’s aggressive policies. He was part of a coalition of chiefs who were older, wiser and had experienced the might of the American army under good leadership. Five Medals personally knew William Henry Harrison. All the chiefs were aware of the recent outcome of tangling with Harrison and it didn’t require any special genius to predict the future if they continued on that path. For the Dearborn campaign, Five Medals and his warriors stayed home.

Wells’ orders to make haste for Fort Dearborn had a deeper and more personal urgency. You see, the fort was commanded by Captain Nathan Heald and his wife Rebekah was with him. Her maiden name was Wells and she was William’s niece. Her father, Williams older brother, was regular army Colonel Samuel Wells. William was committed to her safety. What nobody knew was that Dearborn was the beginning of a coordinated general attack across the region.

Wells arrived at Dearborn and with Heald, decided they would abandon the fort and leave if the natives would guarantee their safety. The agreement was made on August 14 and on the 15th, the 93 U.S. Regulars, militia, women and children left the fort. Then, the Natives attacked, killing 52. There are varying accounts of when, where and by whom the first shot was fired, but the end result is well documented.

Heald had made a deadly blunder. He had agreed to leave the fort and all provisions intact but overnight decided to destroy the gunpowder and the whiskey, the very two things the Natives most wanted. Heald and Rebekah survived, but William Wells was killed in action, ending the life of a vital character in the region’s history.

One of the survivors made his way to Fort Wayne to sound the alarm and under the weak leadership of an alcoholic captain, the fort began its meager preparations. Five Medals was also under assault. He was not in favor of these hostilities. His great ally Little Turtle had died just a few weeks prior, taking his influence with him to the grave. Tecumseh and other chiefs following him were stirring up the younger men in all of the villages. Five Medals faced a choice; either he led his own warriors or he would lose his position as the principal chief. It would be safe to conjecture that the war had come into his back yard and aside from the external political pressure, he felt compelled to take action and protect his village and its occupants. This was not the world he had worked to build.

Five Medals arrived at Fort Wayne as a co-leader with Winamac, who had been instrumental in the attack on Dearborn, and on September 5, 1812 the fort was attacked. The attack was repulsed and a siege began. Meanwhile, General Harrison, who was in Newport, Kentucky received word of the siege and also orders to hurry North and relieve the siege. The race was on. Harrison’s spies told him that Tecumseh with several hundred warriors along with 150 British regulars plus artillery were also on their way. On September 11, Winamac and Five Medals mounted another attack, took several casualties and failed to take the fort. Their scouts advised that Harrison and his army of 2200 would be there within hours and that there was no sign of Tecumseh. The Natives made the decision to disengage and melt away. It was the right decision as the combined reinforcements of Natives and British were stalled by the high water along the Maumee River and ultimately turned back.

Harrison arrived on September 12 and the siege was officially over. He immediately dispatched two expeditionary forces to chase down the Natives. One force under Col. Simrall traveled West after Winamac and the other traveled North in pursuit of Harrison’s old friend, Five Medals. That force was commanded by none other than Col. Samuel Wells. It’s thought-provoking to consider the colonel’s emotional attachment to his pursuit of Five Medals. Though he was a professional soldier, his daughter had barely escaped a life and death situation and his brother had been killed at the hands of, in his mind perhaps, these same Natives.

Wells arrived at Five Medals village and it was empty. His troops proceeded to burn it and then returned to Fort Wayne. Five Medals was on the run. Winter was coming and all his provisions had just been destroyed. The village made the 200-mile journey to Detroit and settled as best they could into camp.

Detroit, now under British control had few provisions and the Winter of 1812-13 was a starving time. Here is one account: “As livestock and dogs in the area disappeared, the Natives hunted down deer, bear, porcupine and raccoon and augmented the meager rations with sun-dried whitefish, parched corn and maple sugar. When these gave out, they nibbled crab apples, wild grapes, chestnuts and cranberries. During the Summer of 1813, a mysterious epidemic (possibly whooping cough or typhoid) swept the region, ravaging the malnourished Potawatomi and Wyandot of the Detroit country and the Ojibwa along the St. Clair River.”

During the summer of 1813, Colonel Richard Mentor Johnson of the Kentucky Mounted Militia took command at Fort Wayne and decided to make another sweep through the area to be sure no Native forces were still present. He had heard reports that Five Medals was back. On June 13, troops re-entered the village and afterwards, Captain Robert McAfee wrote, “…an early start and passed over the swamp and brush wood six miles this side of [the] Elkhart [river]with as much difficulty as ever an army marched, wind and mire beyond description, as soon as we crossed the river we formed and marched in order of battle and surrounded Five Medals Town and found it evacuated.” It was a wet early Summer. Johnson continued North arriving at the St. Joeseph River somewhere between present day Pine Creek and Bulldog Crossing, straight east of present-day Elkhart, IN. He wanted to cross but high water prevented it so he traveled east crossing Sheep Creek and the Little Elkhart before turning North again following the St. Joe, crossing the Pigeon River and arriving at White Pigeons town, which he burned. Journal entries remark that they had found the Military Road from Chicago to Detroit (U.S.12).

Johnson returned to Fort Wayne, but by October would be in Canada just east of Detroit preparing for battle.

Meanwhile, at Detroit, British General Proctor was desperately trying to get 5M and other chiefs to combine forces and move into Canada to join Tecumseh and his army. 5M was stubbornly holding out. They were starving and they weren’t sacrificing themselves for the British unless their villages were fed.

In early September, the factor at Montreal, Major General Rottenberg told Proctor that food and winter clothing was on the way from Quebec. Proctor knew it was a lie but fed the information to the Natives anyway. By late-September, no ships had arrived and Five Medals along with several other chiefs refused to budge.

On October 5, 1813, the Battle of the Thames was fought and the Americans soundly defeated a combined British and Native force. Tecumseh gave the last full measure and was killed in battle. Legend has it that Richard Mentor Johnson was the instrument of Tecumseh’s death and, as Harrison rode the Tippecanoe victory to the White House in 1840, Johnson rode his legend to the vice-presidency in 1836.

In 2013, the Five Medals event coordinator had an idea to recognize this Kentucky statesman, militia colonel and future vice-president of the U.S., who had ridden across the event’s home county 200 years ago, by seeking any living descendants and inviting them to the event to commemorate the bicentennial of Col. Johnson’s exploits. Three sisters, the sole remining descendants were indeed located and accepted the invitation to attend the event!

While the War of 1812 would fight on for well over another year, it was effectively over in the West and the Native American presence was both diminished and forever changed.

Five Medals remained in the Detroit area and appears in History at three more treaty signings. At the treaty negotiations for the second Treaty of Greenville in 1814, Five Medals words were again recorded:

“Father, listen! You want to hear from your children the Potawatomi, the voice of their warriors. I never, when I have anything to say, tell it as stories; I speak seriously, and hide nothing; I speak plain, and direct to the point. Father, we know the situation we were in, when the British left us at Detroit, and you took us by the hand; it is this has brought us together at this time. Our younger brother’s, the Miamias, have been mistaken in saying they kept their warriors and people together; it was me, Father, who kept them all together. Father, the Great Spirit hears me; he knows I tell the truth; he knows I do not hide what I have to say, but I speak right out. I have found great difficulty in speaking about the things which have passed during the war; it would be better to drop that subject at once, and speak of it no more. Last fall, father, when we took you by the hand at Detroit, many of the Kickapoos, Miamias, and Potwatomis, were afraid to speak to you; they asked me to speak to you, and beg you to have pity on their women and children, and I did so. Father, I remember well what I said to you; it is fresh in my mind; you then presented the hatchet to us, and we took it up. Father: I then told you we were not afraid to receive the hatchet and war mallet; we looked at our origins of generation, and found we were men; we told you we were men and warriors; we know not why our brethren, the Miamias, are trying to hide these things, and do not speak out boldly. Father, the time we met at Dayton, I advised Mr. Johnston not to present the tomahawk then, as there would be more of your red children collected here; it would be better to present the hatchet here, and that the Potawatomis and Miamias would receive it here. Now is the time, father; if you raise the hatchet and present it to us, we will take fast hold of it. If you now present the hatchet, none of your red children will refuse it; I am certain your views will meet with general approbation. I speak plain. I thank the Great Spirit I hide nothing.”

Five Medals died sometime between 1820 and 1829.

Five Medals, Wonongaseah, was a great leader, a man who came to peace by surviving the crucible of war. Using innovation and assimilation, he fought for the survival of his people against all comers, whether the White-Americans or other Native-Americans. He was caught solidly in a war between two worlds and we honor his memory by believing he did the very best that anyone could imagine given the time and place.

The mission of the 501(c)3 Five Medals Living History, Inc. is to engage and educate our youth and our citizens on our local history and in doing so, keep the Five Medals name alive so that we remember the greatness, the faults, and the humanity of individuals, both European-Americans and Native-Americans who walked this land before we did. Thank you.

Respectfully submitted by Mike Judson

Sources:

American State Papers. Indian Affairs Vol. 1 pp. 828-836

Antal, Sandy. A Wampum Denied, Proctor’s War of 1812

Clifton, James A. The Prairie People: Continuity and Change in Potawatomi Indian Culture, 1665-1965

Bartholemew, H.J.K. Pioneer History of Elkhart County

Edmunds, R. David. The Potawatomis, Keepers of the Fire

Ibid. Redefining Red Patriotism

Harrison, William H. Discourse on Aborigines

Hopkins, Gerald T. Baltimore Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends

Ironstack, George. Various Excerpts

Jackson, John. Interview, Goshen Democrat ca. 1872

KansasHeritage.org. Potawatomi Treaties

McAfee, Robert B. History of the Late War in the Western Country

Prucha, Fr. Francis Paul. Indian Peace Medals in American History

Web. World Wide

Wycoff, Larry. Academia.edu Potawatomi Treaties with the United Sates 1789-1867

© 2024 by Michael Judson. Used by John Frank Jarboe and reenactingschedule.org with permission of the author.